The combining sign ़ NUKTA is used in Indic scripts for transcribing sounds

for which distinct characters do not natively exist in a writing

system. The name of the character is derived from the Arabic word نقطة

nuqṭah (simplified in Indic romanization as nukta)

“dot”. The NUKTA is used in Devanagari and related scripts of northern

India for expressing sounds not commonly used in Indo-Aryan languages,

mostly those that originate from Arabic and Persian. It is also used

natively in scripts such as Bengali and Tirhuta for distinguishing

between characters that have nearly identical graphical structures.

Although now used quite frequently in modern Indic scripts, the NUKTA

is not part of the traditional character repertoire based upon the

representation of Sanskrit phonology. As one might expect, the NUKTA

is not attested in historical Siddham materials as the usage of

Siddham is largely restricted to the representation of Sanskrit.

I was, therefore, surprised when, during research for my

proposal to encode the script in Unicode, I stumbled across the

following sample

at the Mandalar site

showing usage of NUKTA in Siddham text as:

The above excerpt provides the

translation or transliteration of English “tattoo” in Sanskrit,

English/Hindi, and Japanese. The Sanskrit वेध vedha does

not truly translate as “tattoo”, but carries the connotation of a

“piercing”, “puncturing”, or “perforation” (√ व्यध्); the

English/Hindi ततू tatū is simply a transliteration of English “tattoo”

(which also might be rendered टैटू ṭaiṭū, using retroflex

letters instead of dentals); and इरेज़ुमि irezumi, which

is the transliteration into Siddham of the Japanese word for “tattoo”,

入れ墨 irezumi.

Of interest is the usage of NUKTA in

writing the word इरेज़ुमि. In general, the NUKTA is written with a

letter that has the closest phonetic proximity to the target sound.

Here, the NUKTA is combined with SIDDHAM LETTER JA (/ʤ/) for

representing /z/. When NUKTA occurs with a consonant to which a vowel

sign is attached, then it is ordered in encoded text immediately after

the consonant and before the combining vowel sign: JA + NUKTA + VOWEL

SIGN U. The positioning

of the NUKTA with regard to the base letter depends upon the shape of

the letter and the presence of any below-base vowel signs.

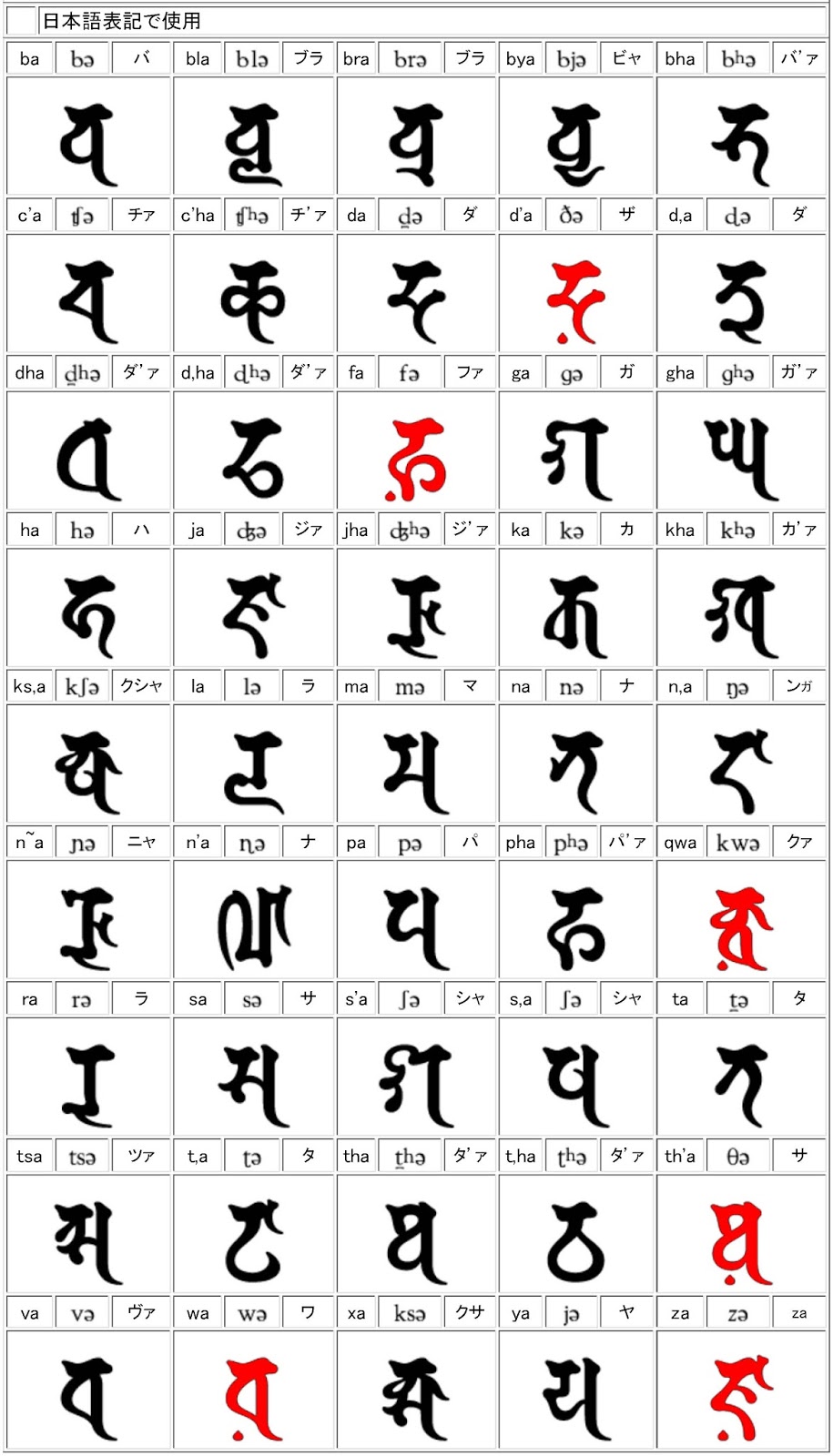

The Mandalar site has a chart

that shows the usage of NUKTA with other consonants for representing

fricatives and other sounds:

The introduction of the NUKTA in Siddham is a

surprising innovation. I have yet to investigate the issue fully, but

at first glimpse the usage of NUKTA suggests that modern users of

Siddham seek to extend the script by adopting features used in Indic

scripts. Such borrowings show that Siddham is quite alive in Japan and

that its usage is continually being extended beyond traditional

contexts. Indeed, the Mandalar site displays these innovations under

the banner of 現代悉曇 gendai shittan or “modern Siddham”:

In order to support such usage, I

proposed the character for encoding as U+115C0 SIDDHAM SIGN NUKTA. It

corresponds to characters such as U+093C DEVANAGARI SIGN NUKTA and

possesses the same properties.

I am curious to know the

history of NUKTA in Siddham and the rationale of the gendai shittan

user(s) who first used NUKTA in the script. Was the idea motivated

by the usage of NUKTA in modern Indic orthographies? Was it influenced

by Unicode? Does the ‘dot’ have ideographic interpretations?