It’s sort of a reverse Rorschach Test: if I see

a blank slate, my mind will fill it with orthographic

imprints. Usually ethereal calligraphy, more recently,

translucent epigraphy. I’ve always marvelled

at the craftsmen who meticulously engrave complex scripts upon

marble facades and copper plates; bringing a blank slate

to life with visible language. I recently had a chance to

materialize my orthographic fantasies.

In early December 2013, I attended an

open house at Equinox Studios in the Georgetown neighborhood of

Seattle. The artists had flung open the doors

of their studios for the public to experience

the spaces where inspiration meets the workbench.

In one space an artist swung a wrecking ball into massive, ornate glass

sculptures. In another, iron-wrights lit up the sky with

pyrotechnic displays emanating from giant, intricate lattices

and delicate cut-metal trees. While watching these

industrial artists cast light and sound into the night, a

more silent performance in one corner of the studio caught my ears.

As I walked over I saw stacks of sandstone blocks

and people hunched over tables. I peered over the shoulder of a

couple and saw them carving the logo of the

Seattle Seahawks into one of these blocks. A few feet away,

metal workers fed wood into the blazing mouth of a

furnace. I watched as a pair of workers reached into the furnace

with a heavy metal yoke and extracted a crucible filled with

bubbling liquid. Another worker collected finished blocks with

carvings and placed them on a metal rack resting upon a bed of

black sand. At her signal, the bearers of the crucible inched

over to the rack and steadily poured the molten liquid into each

block. Further along the perimeter, a worker cracked the cooled

blocks to release a metal tile, each bearing an

embossed image of what has been etched into the block.

I was engrossed by this process of sandstone etchings being

formed into pictographs on steel and nearly forgot about the

rest of the open house. Some of my companions wandered onto the

other installations as I grabbed a sandstone block and

found a spot at the table. I began thinking about what

I would want to see wrought in steel. Luckily, my friend

saved me from writer’s, um, block by exclaiming

“Oh, write my last name in Hindi!”.

For the next 45 minutes I stood hunched over my block,

sketching her name first in pencil, then lightly tracing it with a

carving tool, then going over the grooves repeatedly until the

depths reached a quarter of an inch. Then the devil of details

arrived and he sat on my shoulder as I tried to coax the stone

to yield curves that resemble those of inked letters. When

I finished, I brushed off my shoulder and handed the finished

block to my friend, who ran her finger over the grooved of the

etched imprint of her name in reverse. Thumbs up. She passed it

onto the metal worker, who sprayed it with a graphite coat and

set it on the rack. We watched as the two crucible bearers

arrived with a fresh trove of molten steel and poured it onto

the carving…

The experience at Equinox loomed in my mind. I still wasn’t

sure what I wanted to see cast in metal. A few days later it

struck me while I was researching variant letter-forms used in

Khojki manuscripts while listening to Raageshwari Loomba’s

rendition of the Ismaili ginan “Aaye Rahim Raheman” by

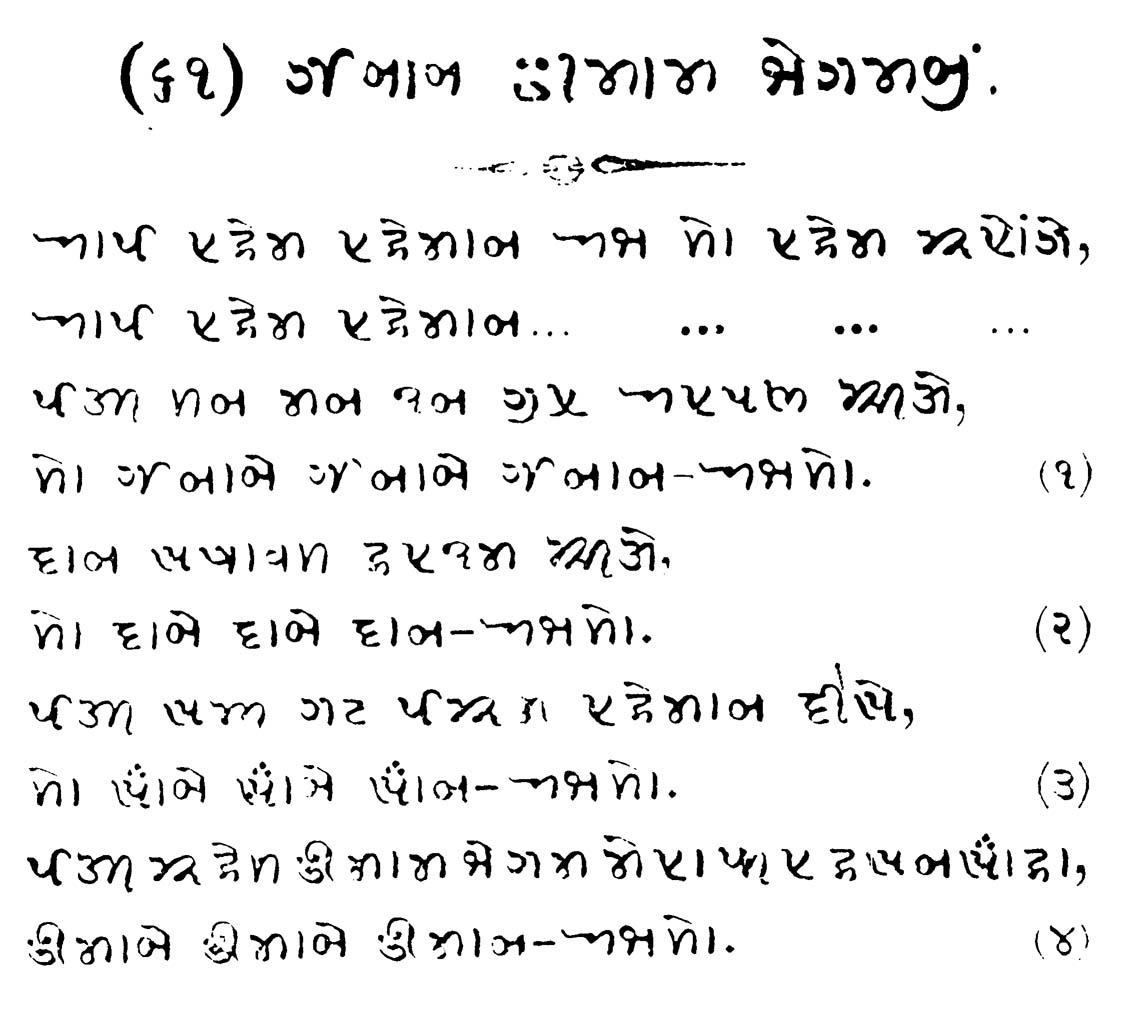

Imam Begam. I read the ginan in a printed Khojki book earlier in

the month:

I wondered if I could reproduce the

letter-forms that Laljibhai Devraj had cut in Germany in 1903

for the first ever Khojki metal types, which he used at his

Khoja Sindhi Printing Press in Bombay. I thought it

might be nice to do an etching of “Aaye Rahim Rahman”, the

ginan which inspired me to think about a Khojki etching

in the first place, but that seemed a bit ambitious. After all,

I had only done one etching. So, I thought of the next best

thing I would want to etch in Khojki…

But first, I would need my blank slate. My friend contacted

Alair Wells, a talented sculptress and metal artist, whose

studio Tinder Heart

Metals at Equinox was hosting the metal working during the

open house. I described my idea to Alair, who was excited

to help. We produced a wooden cast for the block by

using four 2” x 4”s and affixing it to a plywood board. Then

Alair cut an 8” x 10” block from a pine board and we fixed that

to the plywood. We poured Washington grade 7 white silica into

the cast to measure the amount of sand we would need. Then

after we placed the silica into a bucket, Alair and my

friend mixed a catalyst and bonding agent into it, mixed

vigorously for minutes, and then poured the preparation into the

block. The 25 lb. sandstone block turned out beautifully:

Now, I had my blank slate. Then, I chose my tools:

a ⅜” nib, a ⅛” nib, and a needle point:

The first step was to sketch out the Khojki text using a pencil.

The text must be etched as a mirror image so that the embossing

on the tile will have the correct orientation. I had thought of

making a stencil by printing out the Khojki text in reverse and

cutting out the letters using a fine blade, but the glyphs of

the only Khojki font I have do not possess the sort of modulated

strokes I desired for the etching. So, I decided to do a free

hand rendering of the text in reverse:

I then performed an initial etching. I held my breath quite a

bit during this part. Unlike writing on paper or composing in

typesetting software, you really cannot ‘erase’ or ‘undo’ an

erron without having extra

silica and bonding agent on hand. I lightly scraped the ⅜” nib over the sketch I made:

The first phase of the etching of the upper portion of the block

is shown below. The grooves are shallow. I would eventually

deepen the routes:

Then time to sketch out the text for the bottom portion of the

etching. I could have sketched out the entire text first, but I

had a feeling that my palm would just smudge the graphite.

I used the broad nib for the text of the upper portion. It

produced a very pleasant width and modulation that

resembled the style of Khojki I wanted to emulate.